All That Has Been Taken and Changed: A Guest Post about life with Long COVID from Steph Fowler

We’re delighted to share a Substack post from Steph Fowler, a chronically ill & disabled neurodivergent therapist/educator/writer/COVID long-hauler, who’s give us permission to re-publish their moving piece from today about life with Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More and everything they’ve lost from their previous life. We encourage folks to read their Substack posts at https://substack.com/@misfitmentalhealth, and subscribe if you’re so inclined. You can read more about Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More on our webpage about it.

It was early 2020 when my body started to betray me. Despite going to the gym a few times a week, I started to struggle to get through what had been a standard workout. Running 3 miles had been part of my routine for quite awhile, and though I wasn’t setting PRs, I had gotten to a place of being able to do that distance at the end of gym-time with relative ease. But something started to change. After a quarter mile, my muscles burned, I could not catch my breath, and all the energy evaporated from my body. I told myself that I must just be “out of shape” and need to push harder. I switched up my pre-gym fuel and I curated new playlists. I took the “power song” that I used to push through mental blocks when I felt like quitting in the middle of a run, and I put it on repeat – but Billy Idol and the driving beat of Rebel Yell couldn’t compete with my body’s breakdown and refusal.

I had started having other changes to my body, too, but I had assumed they were unrelated. Among them were having no energy no matter how much I slept, along with strange pains and abdominal discomfort. I went to urgent care where they threw some antibiotics at me, and when those didn’t work, I was given different ones. I saw a doctor who ran so many tests at once that I passed out during the blood draw because of how many vials were needed. I saw a specialist who did some imaging and recommended surgery to look for the source of the pain.

So on March 4, 2020, I found myself in the hospital, laying in a gown in the pre-op area watching the news of COVID-19A disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, leading to respiratory illness. spreading through China and Italy. My concerns had been growing in the preceding weeks, as the WHO had started to warn of the possibility of a pandemicA global outbreak of a disease.. I’d already been concerned enough that a week before my surgery that I had posted questions in various online therapist groups, asking for people’s insights about the logistics of offering virtual therapy sessions….”just in case”. As someone who owned and ran my own business, I wanted to be prepared.

I took some time off after the surgery to recover, and from the couch I watched as the virus came closer and made it to New York. When I talked with people I knew, I tried to gauge how others were feeling and what they were thinking. It was apparent that I was one of few people who considered it a serious concern. Two days after I returned to the office from medical leave, I ran into another therapist in the office building’s kitchen. I made a remark about how wild the news was and got a sort of blank stare in response.

“Oh, you mean that virus? My wife’s a nurse and she’s not worried. It shouldn’t be that bad.”

I was not reassured, and I decided preemptively to cancel my therapy sessions for the next day, Friday the 13th. It was on that day that our governor announced schools would close the following Monday for 2 weeks. I felt a real sense of dread about what was coming even though few others seemed to. In anticipation of being at home for a while, I stopped by my office to grab some things I might need. On my way home, I popped into the local Irish pub where I had become friendly with the staff, after hosting several parties there over the years and stopping in for dinner regularly during the months I was launching my business. I wished them good luck before the hecticness of the annual St. Patrick’s Day festivities began.

I didn’t know that would be the last time I’d see many of them. Or the last time I’d set foot in the warm, cozy place where I’d celebrated milestones by the fireplace and mourned major losses with my favorite comfort food. And I didn’t know that would be the last time I’d be in a restaurant or public place with any sense of ease at all.

I saw the reports of mass deaths, had heard that a pandemicA global outbreak of a disease. had officially been declared, and knew the virus had already been reported in Illinois – which is why schools would close in a couple days. But that weekend, I watched on news reports and my social media feed as the mass of St. Patrick’s Day celebrants seemed unaware, ignored this, rebelled against it, or believed it wasn’t serious.

This disconnect started to grow in the weeks and months that followed. Morgues filled up and freezer trucks were brought in. Ambulance sirens were audible and heard with eerie frequency both in my neighborhood and from my clients’ end during our virtual sessions. Yet, in conversations and on various online platforms, I noticed conflicts between people who were listening to health experts and those who expressed annoyance that they couldn’t go to parties and do the normal things they wanted to. At the peak of the pandemicA global outbreak of a disease., I witnessed the pain from healthcare workers who were on the front lines and were absolutely traumatized (and repeatedly re-traumatized) by the lack of protections, lack of support from their employers, and repeated reckonings with the limits of care they could provide against this novel virus. Other essential workers agonized over whether to quit their jobs and lose financial security, or risk contracting the virus that was killing and hospitalizing people in order to keep their jobs at grocery stores, pharmacies, and in other public services. At the same time, I saw and heard people rage against restrictions or become angry about not being entitled to get haircuts, go to restaurants, or access other things they wanted and were used to, as if they did not see or know what the stakes and public health risks were. All the while, I was trying to support clients through this collective trauma that I was also processing in real-time, figuring out how to make transitions to my business to keep it afloat, and still trying to sort out new health issues that no one could solve.

I never could have predicted how much these early days would foreshadow or become a new template for my life.

I fought to keep up with everything but was exhausted and developed new and changing symptoms that made it hard to function. Suddenly, I’d develop incessantly itchy hives for weeks, then they would disappear. Then gastrointestinal symptoms started, and for months I had what I can only describe as full-body, all-consuming nausea. Different body systems went haywire, one after another, but disappeared before I could get an appointment with the appropriate specialist. However, the constants for me were exhaustion-but-struggling-to-sleep, feeling like my limbs were weighed down and I was moving through mud, and “brain fog”. At one point, the cognitive dysfunction got so severe that sending a simple email with one attachment took me 45 minutes because I kept forgetting the steps and what file I needed to look for. At some point I got a full neuro-psych evaluation which was a roller-coaster of insulting relief, showing I wasn’t making this up or exaggerating, but then it became really real.

I had to reduce my work to part-time, and I was doing all sorts of appointments to try to get to the bottom of why all the other tests were normal and the usual medical advice made me feel worse instead of better. Having to go to any medical appointments in person and risk infection was nerve-wracking, but some of the tests had to be done in-person. Little did I know I’d one day miss the required masks, symptom screening, contact tracingIdentifying and notifying individuals exposed to an infectious person., and social expectation to stay home if there was even a concern about being exposed to someone who might be sick.

I spent the first half of 2021 having 3-4 appointments every single week for 6 months straight. Doctor appointments. Blood tests. Imaging. Somatic therapy. Physical therapy. Acupuncture. Holistic medicine consults. I burned out and by July I crashed so hard I had to take a month off work in which I basically did nothing. I would eventually come to be diagnosed with Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More in early 2022 after having to harass my way into a specialty clinic that, at first, said they would not see me. I stopped counting all my out-of-pocket costs from trying to get answers or address my symptoms after I hit $30,000 around midway through that year. Maybe lots of people have that kind of money to burn, but I’d only been able to work 10-12 hours a week for years at that point and for years since.

Initially, like many people, I tried to address isolationSeparating sick individuals from healthy ones to prevent disease spread. and did virtual hangouts and went for walks outside with friends. When things started to reopen, it was nice to see familiar faces and know that we were smiling at each other behind our masks. Despite having to conserve energy for days in advance and plan to spend days wrecked and horizontal afterward, I made it to two outdoor weddings and one outdoor party in 2022. It felt like perhaps some normalcy was on the horizon, and I even had a couple months of my symptoms finally starting to slowly improve in early 2023.

But then, despite vaccinations, avoiding non-essential time indoors, and wearing respirators everywhere, my household got COVID in March 2023 from some unidentified exposure, possibly a quick stop pick up to-go food. All improvements vanished, my health worsened, and the Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More symptoms increased significantly. I developed scary speech problems where sometimes, randomly, I could not make my mouth form the words I was trying to say. I had a resurgence of insomnia that kept me up until 6-7a.m. and a relapse of migraines I hadn’t had since college. Dysautonomia also appeared, often making it difficult to stand in place for even a minute and making me really intolerant to extreme temperatures. Even now, multiple times a week, I get alerts from my smartwatch that I have tachycardia – from such “exertions” as stirring a pot on the stove or having a conversation while sitting down. If the barometric pressure shifts, I can get the sensation of wool filling up my skull and be completely unable to find a coherent thought.

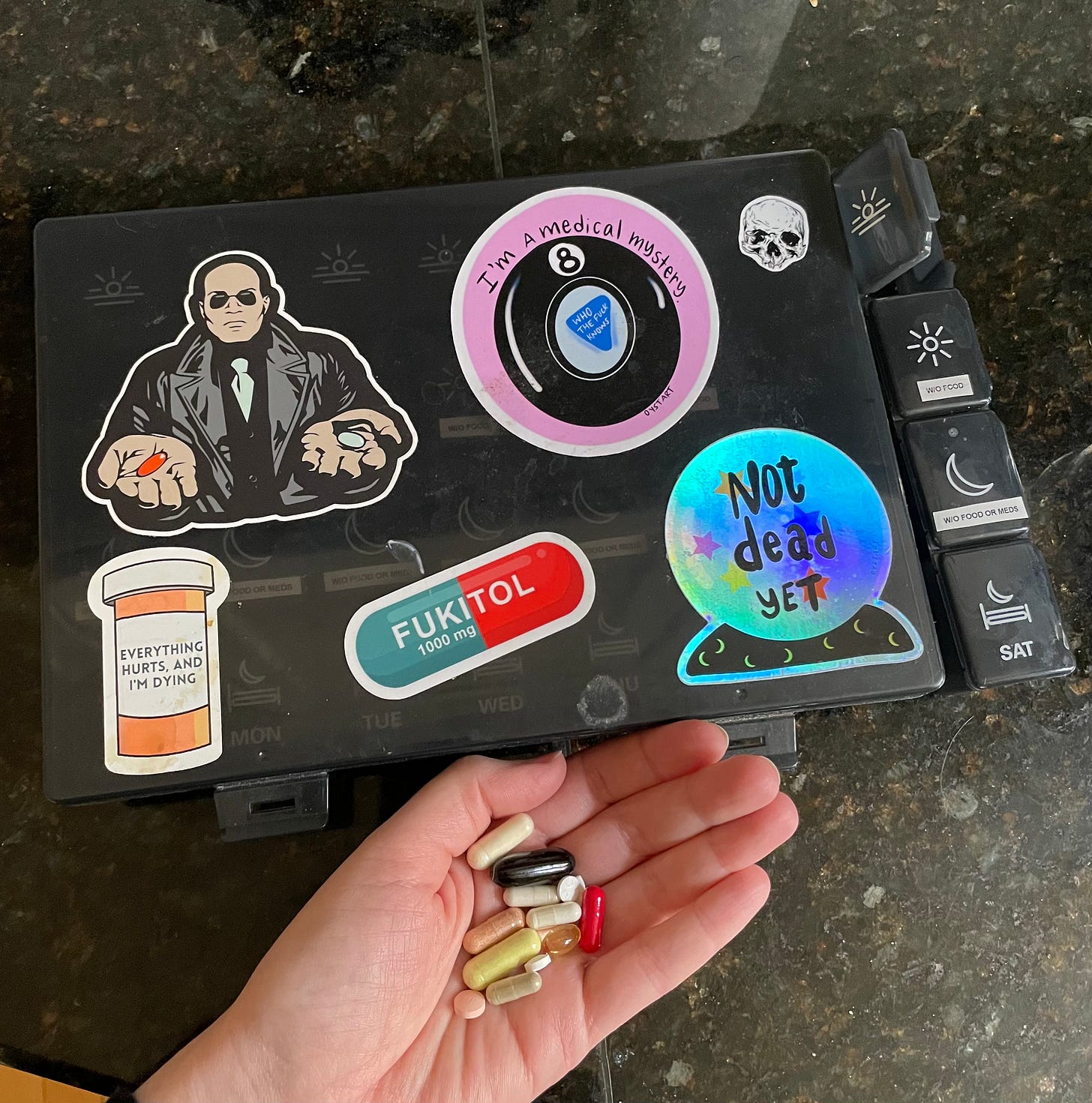

Steph’s holds a handful of pills – only one morning dose – next to a large pillbox decorated with stickers, The Saturday mini box shows each day has four compartments.

Despite trying everything I’ve been offered in terms of off-label medications, supplements, natural remedies, and various therapies over 5 years, I don’t really have much to show for it. Maybe they have helped me avoid becoming bed-bound, like happens to many people with Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More. It’s now exceptionally difficult to go beyond a 6 block radius of my home, and there will be several consecutive weeks that I can’t leave the house at all. My baseline capacity declined to roughly 40% of my previously healthy baseline, and what energy I have needs to be spent on working/earning income, trying to manage my health, life responsibilities, and household tasks. My body is often too drained to engage in any hobbies that require concentration (reading, puzzles, games) or coordination (embroidery, art, other crafts) and socializing is a rare treat. For numerous reasons.

At first when I expressed worries about getting left behind and not getting better fast enough, people rushed to heart-react on posts and send messages of support saying, “Don’t worry, we’re not going anywhere. We’ll be right here!” Eventually the words betrayed the meaning. They (with very few exceptions) have stayed where they were, and I ended up somewhere they don’t want to visit. I have actually gotten many messages over the last few years with invitations to catch up or get together – but I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve gotten ghosted with absolutely no response as soon as I’ve explained what I need to make that happen, tell them I’m now disabled, or request a virtual hangout instead. Eventually my social media posts (the only option left to connect) were also met with silence and unfollows. This abandonment is a common experience among the estimated 20 million Americans and 400 million people worldwide who have experienced Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More, along with the loved ones and allies who still engage in practices that protect us from further health declines.

When the grief creeps in, I start wondering…Who doesn’t believe me or thinks I’m exaggerating? Who does believe me but doesn’t want to be reminded of COVID and what it can do? Who is avoiding me because I represent the reality that anyone can become sick and not get better? Who isn’t interested in knowing me anymore because I’ve changed? Who would be interested but doesn’t feel that my access needs are worth the effort? Who thinks that I should just be fine accepting the risks of accumulating more infections and potentially losing what’s left of my wellbeing and ability to work? Who doesn’t even think about me at all?

None of these feels better than the other.

These changes are not just in my personal life. Professionally, I cannot attend conferences or events anymore because they are inaccessible. Even though virtual or hybrid options and masks were possibilities and commonplace a few years ago, these are no longer available accommodations. When I have reached out to multiple conferences to request this accessibility for chronically ill and disabled clinicians, I am told they “don’t do that anymore” if I get an answer at all. I submitted a proposal to be a presenter at a conference last year but mentioned I would need accommodations, and I’ll never know whether I was rejected because of this or not.

What hasn’t been taken away by the virus’s impact on my body has been taken away by society’s lack of imagination, innovation, or willingness to adapt. There are periods when my body could handle some kind of outing, or there are activities that I would save up the energy for or be willing to spend some days recovering from. However, I’ve found only ONE of the spaces, groups, places, or businesses that I frequented before the pandemicA global outbreak of a disease. is actually accessible to me now. I’ve seen in other cities that some museums, theaters, schools, and studios continue to have virtual or hybrid offerings, or advertise specific masks-required days, hours, or classes. I’m envious of that accessibility and inclusion and wish it wasn’t so rare when it seems like the bare minimum way to get a passing grade at supporting these communities.

Society could have followed the wisdom of Semmelweis – the doctor who first realized that disease was not random or inevitable when he discovered that handwashing could prevent the illnesses and deaths he was seeing. He advocated for preventative protocols and saved lives by making these changes. We could have incorporated lessons from the COVID-19A disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, leading to respiratory illness. pandemicA global outbreak of a disease., including the knowledge that virus-spread happens not only from surface contact but from airborne aerosols that can remain in the air for hours. We could have implemented indoor air quality monitoring, started the process of upgrading schools and public spaces to meet the air filtrationThe process of removing particles from the air or liquids using filters. and ventilationThe process of circulating air to improve indoor air quality. recommendations established by the CDC, maintained flexible work and school arrangements or cancellation policies so people could stay home and not spread illnesses, or any of the other public health efforts that have been proven to control and prevent infectious diseases.

Instead, society chose to emulate Charles Meigs, the physician who rejected the new concept of disease spread, despite the proven decrease in death rates. He and his peers were offended at the idea that they could be responsible for causing illness and deaths. Meigs believed doctors were “gentlemen” and “a gentleman’s hands are clean.” (I think of this whenever I hear someone say “Why are you wearing that mask, I’m not sick!” as though they haven’t been around coughing and obviously sick coworkers, family members, transit riders, and other groups of gathered people during a quademic.) We as a society, like Meigs, have also chosen to ignore new information and be offended at the suggestion of taking accountability to break the chain of transmission…even though that was the norm not that long ago. Rather, we normalized surges of multiple infectious diseases that close down schools, continue to overwhelm healthcare systems, cause near constant illness in families, that are still causing new Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More cases and other long-term conditions, which are contributing to rising rates of disability, and costing the economy $1 to $3 trillion. (That’s not a typo.)

We’ve decided that individuals who want to avoid these outcomes must take on the collective public health burden to protect themself in any space where they share air with others, which is a Sisyphean task. I, along with the millions of other COVID Long-haulers, medically vulnerable and high-risk folks, and health-conscious people are forced into an impossible dilemma: assume the significant risk of becoming sicker, further disabled, or dying from another infection OR go without or avoid things like healthcare, shopping trips, or the optional but enjoyable ways to scrape together any kind of quality of life. What were temporary calculations and adaptations for others became my new normal, along with millions of others. And we are struggling.

A black sign with blue writing that says “We’re All in This Together” is pictured in a dumpster with some trash.

I don’t understand why or how an entire society went from “we’re all in this together” to accepting and supporting this inhumane existence that’s been forced upon multiple vulnerable groups, some of which are supposed to be protected classes under the law, without a second thought. Maybe it’s because people want to believe that individuals can do enough to prevent our own illnesses? But I am among the many who have learned the hard way from my reinfectionBecoming infected again after recovering from an earlier infection. that vaccines don’t always prevent transmission and one-way masking by individuals is not as effective as collective masking, especially when multiple airborne diseases are running rampant without any effort to ventilate or filter shared air.

To add insult to injury, those who have learned and integrated new information and adapted in ways that protect themselves and others, are now being pathologized and ostracized – like Semmelweis. Rather than seeing his practices that reduced illness and death as revolutionary, the medical field took decades to give any merit to his discovery – only after Semmelweis had his ideas so vehemently rejected that it contributed to mental health decline. He was committed to an asylum where he was beaten so severely that he died from the injuries. As the efforts to ban masks continue to grow, I see the potential for truly awful outcomes.

I worry about how long this will go on and wonder what it will take to get a different outcome. We don’t have the decades that it took for Semmelweis’s theory to get traction and finally be integrated. People have lost too much already and had their lives on hold for half a decade. People with Long COVIDPersistent and new symptoms following recovery from acute COVID-19. More have been told to be patient and that treatments would be coming – meanwhile the U.S. wasted $1 billion (again, not a typo) on supposed research that went basically nowhere. It’s cost us careers, relationships, pieces of our identities, immeasurable sums of money, financial stability, emotional stability, visibility, connection, and so much more.

I miss kickboxing and the satisfying smack of the connection of my right hook.

I miss training for 5Ks and running in the rain with my carefully curated playlists that matched the beats per minute with my running pace.

I miss wandering around the city on warm days, with no real destination in mind, but always discovering something unexpected.

I miss hanging by the fireplace in the pub that’s now gone and been replaced with some abomination I don’t want to know anything about.

I miss finding weird puppet shows, doing cosplay karaoke, and making elaborate costumes.

I miss reading entire books.

I miss traveling, getting lost, and finding my way again.

I miss picking my own produce at the grocery store.

I miss having any degree of spontaneity or ease with making plans, or even in my quiet days.

I miss having an ounce of predictability about my body.

I miss my independence and consistency. Fiercely.

I miss being able to trust people and the innocence of life in 2019.

I miss having at least some ideas of what my future and life could possibly look like, or at least feeling like it wasn’t completely in other people’s hands.

I miss the privilege and naivete of not knowing how much people hate, ignore, and are apathetic toward people who inadvertently remind them that bad things happen that don’t always make sense and can’t always be fixed.

I miss being connected and belonging somewhere, not just tolerated…or not having to worry if I won’t even be tolerated and will be harassed.

I miss when my existence didn’t represent something people are trying desperately to forget.

I miss when I would tell people a story and I would watch them listen intently instead of seeing their eyes glaze over as they dissociate.

I miss (which actually shocks me as an introvert) striking up a conversation with a stranger, discovering we have something in common or view something about the world similarly, and walk away feeling heartened by the sense of shared humanity.

I miss that sliver of a moment in time after everything fell apart when we got a taste of how different things could be, when we mattered to each other, and when we talked about never going back to the way things were before…

If everything else remains lost, I hope beyond hope that we can somehow get back to that.